TAKLAMAKAN (Xinjiang, China)

14.2 Power place

Names

– Taklamakan

– Takelamagan Shamo

– Taklamakan Shamo

– Tak, after the original inhabitants (Prof. J. J. Hurtak)

The name “Taklamakan” comes from the Uyghur, and its meaning was long unknown. Most sources give the following rough translations:

– Desert of death, sea of death

– Place/site of no return

– Enter and you will never return

– You can enter, but you will never find your way out

– Land of the cottonwood

The dictionary says that studies conducted by Quian Boquan of the Uyghur dialect have shown that Taklamakan means “land of the cottonwood” because “Takli” comes from the Turkish word “Tohlak” or “Tohrak”, meaning “cottonwood”.

Geomancy

The landscape is as endless as an ocean, and the desert today is extremely hot and dry. It is a perceptible transformation from earth to stone and sand dominated by the winds. The place was originally fertile, and I thought the energy was very pure and clear.

Power point

The actual power point is located in the desert’s center, which is inaccessible.

Prof. Hurtak’s hypotheses confirm this, saying the place is located almost in the center, but slightly closer to the Himalayas. Mazar Tagh is the nearest structure; I made it that far during my journey in June 2011, but an approaching sandstorm stopped me from proceeding any further.

– Corresponds to: root chakra, body

– Color: red, ruby red

– Dominating elements: water and air

– Corresponding place: Megimi, French Polynesia

14.3 Main structures

So far, no megalithic complexes have been discovered in Taklamakan, but spiritual sources report old sites buried deep in the sand over the course of time. It is said that those complexes are the holy sites of the Lemurians, who created this place by linking heaven and earth. It was a bustling place, as its successor cities evidenced by slowly opening the desert. The Silk Road also ran through it.

The “Unnamed City”, 200 BC

In the 1990s, Chinese and French archaeologists discovered the ancient ruins of a city that had been buried sand right in the center of the Taklamakan Desert more than 2,200 years ago, around 200 BC. The round city wall was 995 meters long, and its height varied between three and eleven meters. The archaeologists also found traces of city gates to the south and east, and assume that there were four in each cardinal direction. The city walls were made of cottonwood and Tamarisk trees and covered with mud. A protective rampart of boulders was built on the outside and filled with tree branches and roots, reeds and slack.

According to my research and interpretation, this complex was built by the Tocharians over the one their ancestors built and in the knowledge of the site’s significance and energy.

Subterranean structures

No underground complexes have been found. The megalithic complexes on what was originally the earth’s surface are buried hundreds of meters beneath the sea of sand, which makes discovery and excavation impossible.

Other structures in the region

Mazar Tagh, 200 BC

Today, this complex is the nearest to the actual main power place and is attributed to the Tibetans, who also knew of the site’s significance and its connection to Mount Kailash (see page 146). “Mazar Tagh” means “old Tibetan fort”; it once dominated large parts of Taklaman. The complex has been dated to between 400 and 800 AD and the old core to 200-100 BC, which corresponds to the “Unnamed City” in its center. Later wall paintings suggest Indian, Greek and Persian influence from the seventh to the eighth centuries and indicate that the site was of strategic importance.

Numerous old cities beneath the sand

Archaeological sites are well-preserved because of the desert’s dryness, and since China opened the area for archaeological cooperation in the 1990s, astonishing insights have been gathered. In Taklamakan, for example, some sunken sites have been discovered, which became uninhabitable because of the desert’s expansion or because the rivers that watered them dried up. The archaeological finds suggest Tocharian (Eurasian), Hellenistic (Greek) and Buddhist (Indian) influences.

We will examine three regions more closely, analyzing ancient cities in the desert’s periphery at Hotan (Khotan), Lop Nor, and Turfan/Dunhuang.

Youmulakekum, 800 BC “The Old City of Round Sand”

In the legends of today’s Uygurs from Yutian, who live 300 km south of the location of the find, the rediscovered city is called “Youmulakekum”, meaning “round sand”. That is why the archaeologists renamed the place of the find “Old City of Round Sand”. The French and Chinese researchers were also surprised to find confirmation of the legend; in contrast to other old cities, no mention of Youmulakekum has been found in historical documents. Nor are there any conventional characters, symbols or other clues that could explain the city’s history. It has survived in the legends, but was probably buried beneath the desert sand even before our era.

The French researcher Francfort said that the city might have been a place in which goods were traded from the west and the east as early as 1,000 BC; agate ornaments that have been found come from the west, and torso ornaments come from the east.

Analyses of satellite imagery and new scientific research have shown archaeologists that the round city was located very favorably, protected within the basin and surrounded by several rivers and dense forest.

The houses in the residential area were located in the northern part of the round city, which was also built largely of cottonwood, as were the city walls and common utensils such as barrels, bowls or combs. Today, however, not one single cottonwood tree is left in this city, a circumstance which reminds me of Easter Island. Archaeologists have discovered more than 20 tombs around the “old city”, of which only three are still intact and in which four mummies were found (see Finds, page 607).

Archaeologists have also found skeletons of many animals, which they believe to show that ranching, fishery and hunting played an important role in the lives of these people, who lived in a country that was still fertile. Irrigation ditches were even found in the areas around the city ruins; they were developed by the so-called Sand People, a mystical people living in the middle of the desert. Traces of wheat and millet, grindstones of different shapes and numerous silos for corn have been found. This high level of knowledge distinguished the Sand People from their neighbors and indicates that they were Tocharians.

Djoumboulak Koum, 500 BC

This ancient find site in the oasis of Keriya near Hotan is called Djoumboulak Koum (“yuansha gucheng” in Chinese) and represents the first clue suggesting a settlement before the Han period and the only settlement known in Xinjiang in the middle of the first millennium BC. Here, too, excavations were carried out by Chinese and French archaeologists in the 1990s, during the course of which a site with an area of ten hectares enclosed by a clay brick wall was unearthed.

It was the center of an oasis-like, densely populated zone measuring 20 x 15 km, or about 300 km².

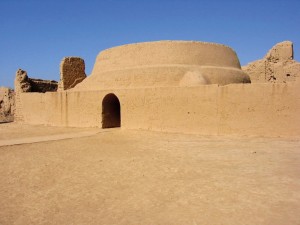

Djoumboulak Koum was a fortification which required huge amounts of material and armies of workers to build. Its massive fortification wall, which was rebuilt several times, is between 2.5 meters and 4 meters high and 4-5 meters wide. It is made of reinforced clay overlaid with a layer of large, raw clay bricks. Its top is reinforced with dowels, and some sections formed the borders of galleries. The fortification wall was traversed by a roofed passageway and adjacent rampart and sealed off with a door of which one wooden wing still exists. The city‘s southern gate was located on the outer end of the hill, the summit of which, at 1,160 meters, is the site’s highest point. Its construction method differs substantially from the Chinese techniques of stamped soil and indicates Eurasian or Central Asian influence.

Here, the Sand People were also engaged in irrigation and stock farming long before the Han period, as skeletons of goats, sheep, cattle, camels, horses, dogs and hens show. The remains of an irrigation network found around the site stretch over several kilometers. It is the oldest known irrigation system in the modern-day province of Xinjiang and refutes the traditional concept that neither irrigation nor agricultural developments were used until the Chinese settlement at the beginning of our era.

The ceramics display similarities to those of the cultures with gray pottery from the southern oases in Taklamakan. Large grindstones and grinding mechanisms made of various stone types indicate contact with the zones at the edge of the mountains. For the people in Djoumboulak Koum, the jade stone that was exported to China in the Bronze Age seems not to have been a luxury material, but an everyday one; they even used it to make grinders.

What is just as astonishing is that Djoumboulak Koum had well-developed metallurgy for working bronze and iron, as indicated by numerous cinder finds. This in turn indicates older knowledge or the early exchange, unknown until then, of goods and craftsmen with the east and China and with the steppes and mountain peoples in the north and the west. The researchers’ statement in the report’s conclusion relating to the history of a place that is actually far older is also interesting. They report having tried to achieve a clearer delineation of the oasis with its capital city of Djoumboulak Koum and finding an even older settlement area which they were not yet able to explore. Several necropolises in which the dead were buried with tucked legs in tree trunk coffins or containers of reed were discovered near the settlement. Because of the dryness, even the dead remained well preserved so that the mummies from Djoumboulak Koum have a special significance for archaeologists (see “Finds”, page 607).

Karadong (Keriya) around the beginning of our era

Until the last decade, the ancient history of the Keriya River was almost unknown, and Karadong was the only known ancient city. Sven Hedin discovered the ruins when he passed through the region in 1898, and Sir Aurel Stein visited the sites and provided new documentation of them in 1906 and 1908. This discovery began what has come to be the well-documented fact that Karadong, like the kingdom of Khotan, was within the sphere of influence of the Indian Gandhara culture despite Chinese sovereignty at the time and the objections of Chinese historians today. Karadong is still considered the capital city of this ancient delta that was settled at the beginning of our era and abandoned at the end of the third century, probably because of the rapid expansion of the desert with its huge, shifting sand dunes.

Dandan Oilik, beginning in 200 AD – “Place of ivory houses”

This is another city that has sunk into the silica sand of the Taklamakan Desert. It is located northeast of Hotan in the district of Quira near what used to be the Khotan river (the Mazar Tagh is further north). Dandan Oilik (“place of the ivory houses”) was discovered in 1895 by Hedin, and Stein conducted excavations in 1900. Since researchers last visited in 1928, the city had been forgotten and locating it again was thought to be impossible.

It was not rediscovered until 1998 by an expedition under the Swiss explorer Christoph Baumer, and the desert sands have since covered it again. There has so far been no explanation for its significance and the incredible name it bears – in the region, place names always bore a meaning, so there must have once been ivory there, even if none has been found. But the natives tell a “fairy tale” about a prehistoric city located there with houses or at least a temple of ivory, which means that elephants and mammoths must have lived there.

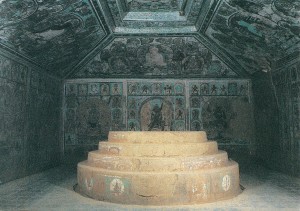

The Dandan Oilik was a historically significant Buddhist center on the Silk Road. Archaeological digs have revealed Buddhist murals from the eighth century, a paper fragment in the Khotanese language and the Indian Brahmi script from the seventh century and memorial tablets from the sixth century that have since been attributed to Buddhism and now reside in the British Museum.

Loulan (Shanshan), 200-350 AD

In the dry Lop Nur lake bed lay the kingdom and the city of Loulan, similar to Karadong and Dandan Oilik. It was first mentioned in 200 BC and then again in 350 AD, when it sank into the desert. Mummies were found there, too (see page 607).

Kocho (Idikutschari), from 200 BC

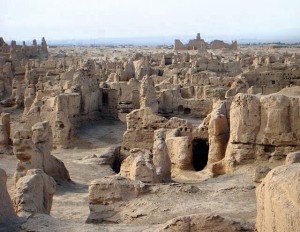

These ruins are located 30 km southeast of the modern-day town of Turfan (Turpan) and are called Kocho (Xoqo in Uyghur); alternative names are Chotscho, Khocho, Qoco or, in Chinese, Gaochang. The archaeological remains are in a place that the natives originally called Idikutschari, the history of which is based on oral legends. It was an ancient oasis city that was built on the northern edge of the Taklamakan Desert in the second century BC. Kocho was a major trading center on the Silk Road and is the only one of these ancient desert cities not to have sunk into the desert; instead, it experienced a renaissance. It was not until the wars of the 14th century that it was burned to the ground. The ruins of the old palace and the inner and outer city walls can still be made out.

Jiaohe from 200 BC, Xituanshan ruins

The ruined city of Jiaohe (Yar Khoto in Old Uyghur, Ya‘erhu gucheng in Chinese), also called Xiaohe or Xituanshan, is an archaeological site near Turfan. It lies around 10 km west of the city in the Yarnaz Valley on a rocky plateau 30 meters high. Pyramid-shaped graves have also been found there (see page 607). According to historical accounts, it was the capital city of the Chisi kingdom (Cheshi quian wangguo in Chinese), one of the 36 kingdoms in the western regions, from 108 BC until 450 AD. The city was chosen and developed as a fortress as early as the time of the Han Dynasty after an older people, whose name is not mentioned, had been subjugated. It had probably also been a city of the Sand People, like Youmulakekum was from 800 BC.

This is just a small excerpt from the book GAIA LEGACY.

14. TAKLAMAKAN (China)

14.1 Landscape 575

– Geography 575

– Geology 576

– Climate 578

– Vegetation 579

14.2 Power place 580

– Names 580

– Geomancy 580

– Power point 580

14.3 Constructions 581

– Main structures 581

– Subterranean structures 581

– Other structures in the region 582

– Pyramids in China 588

– Temple structures 598

14.4 History 600

– Historical History 600

– Finds 605

– Prehistoric history 610

– Builders and peoples 611

– Original purpose 612

– Legends and myths 612

14.5 Spirit 613

– Religions and deities 613

– Spirituality and transmissions 616