RAPA NUI (Easterisland, Chile)

8.2 Power place

Names

– It was called Easter Island (Isla de Pascua) by the Spanish conquerors.

– To this day, its inhabitants call the island Rapa Nui, the same name they give themselves and their language.

– Te Pito o Te Henua, “the navel of the world”, is an older term used by the 15th-century chief Hotu Matua.

– Makatikerani, “eye that sees the sky”, is another name for the aborigines.

Geomancy

The place has unique energies that I would not compare with another of the other places I visited, except for Giza. Alone the location, this barren volcanic island in the middle of the Pacific, more than 3,000 km from the mainland in any direction, enables an innate energy to arise from the airy, windy distance, endlessly as in no other place. In contrast, the volcano and rocks have a very hard, stony radiance and yet remain fiery flowing.

Power point

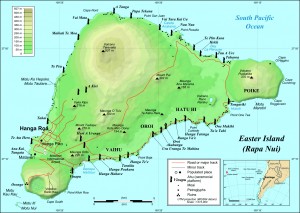

The main power place is located by the Maunga Puhi crater hill near Vaitea, the geographic center of Easter Island and the possible center of the imaginary pyramid (see Fig. 8.58).

The energies here are extremely bipolar and I was able to directly feel the Earth’s magnetic field and overlapping dimensions as in no other place except Giza.

Several months later I read that an expedition of French scientist measured an equally unusual anomaly of the magnetic field here in 1964.

– Corresponds to: crown chakra, spirit

– Color: violet

– Dominating elements: air and fire

– Corresponding place: Giza, Egypt

8.3 Main structures

The emblems of Easter Island are the enormous ahu stone platforms and the monumental moai stone statues standing on them, the mystery of which has yet to be solved. Despite extensive research, their architects, time of construction and actual purpose remain unclear.

Moai – stone statues

The actual name of the moai is Moai Maea, meaning “stone figure”. Archaeologists believe that these statues probably date back to 500 -1700 AD However, their age is fiercely debated because the results of scientific analyses reveal large differences, 400 to 1,500 years and the alternative and esoteric sources assert that they are 2,000 to 12,000 years old.

A meticulous description of all statues still in existence was provided by Father Sebastian Englert, a German missionary who lived on Easter Island from 1937 and numbered and cataloged 638 statues. He wrote several books, including the standard work “The Land of Hotu Matua”. However, the ahu platforms and comparisons indicate that there used to be 1,000 of the colossal stone statues. Today, only 43 moai stand on their ahu, twelve of which have been laboriously restored since the 1980s.

Most of the man-like figures stand between six and twelve meters tall and weigh 40 -150 tons. The longest moai is 20.65 m long and weighs an estimated 250 tons, but is buried in rock on the outside wall of the volcanic crater Rano Raraku (see Fig. 8.17).

Most moai are carved in a similar style, although there are exceptions. The oversized head makes up one third of the entire statue and the face is quite delicately shaped. The eyes have pupils that look directly at the observer and some of the sockets originally held white corals. Most of the noses have nasal wings and nostrils. The mouth is not very pronounced and the chin is broad and angular. The ears are remarkable – most are oblong with elongated lobes, some of which have earplugs but there are also the short ears, whose differences we will discuss (see 386).

Nearly all these stone busts end right below the navel and on some statues, the phallus is subtly indicated.

The largest differences between the figures become apparent only after a second look: the different positions of their carefully chiseled arms and hands, most of which cover the statues‘ stomachs. The moai can also be distinguished by their differently shaped leather loincloths and the knots at the lower back. These chiseled details are not preserved on all figures.

Some of the statues originally wore pukao, cylinder-shaped headdresses carved of red scoria. Pukao, too, are objects of speculation – from the hat to the headdress to the topknot. Although around 100 pukao finds have been documented; most of them near the moai, this number is considerably lower than that of the roughly 1,000 statues. A comparison of the ahu revealed that there are no pukao on the statues on smaller ceremonial platforms, which leads to the conclusion that only moai of special significance wore pukao.

There are three theories about those whom the statues depict: deities, ancestors or famous chiefs. According to the legends of Rapa Nui, the statues are links between our world and the hereafter. They always stood on an ahu, backs to the ocean, with the villages before them. The exception is the Ahu Akivi, where the seven figures face the Pacific Ocean and the legendary Hiva (see page 370).

Rano Raraku quarry

At an impressive height of 150 m, Rano Raraku is a parasitic cone on Maunga Terevaka. Fresh water accumulates in its 350 x 280 m oval caldera, which has always been essential to the islanders‘ water supply and thus their survival. Parts of the south-eastern slope have caved in, creating a steep scarp. The quarries and production sites from which almost all moai were hewn from the rock are located there. The moai were carved out of the volcanic tuff with obsidian chisels and burins of basalt (toki), some of which have been found there. Thor Heyerdahl established experimentally that it is possible to carve the rocks with these archaic tools, but could not determine how the statues were then separated from the flanks of the volcano and moved. The builders‘ productivity was incredible; another 350 statues in addition to the original 1,000 moai have been found in the quarries in all stages of fabrication. There are work pieces whose backs have not yet been hewn from the rock, separated statues not yet carved and dozens of complete statues standing halfway up the slope and buried up to their chests or chins in the earth. The idea of “interim storage” before later finishing is inadequate to explain the number of statues. As early as 1927, German ethnologist Hans Schmidt distinguished between the “ahu type”, with a flat, broad base, and the “Raraku type”, with a wedge-shaped base and posited correctly that the carvers never intended to bring all of them to the ahu platforms. His idea is supported by the fact that 21 statues are located inside the caldera, making them virtually impossible to move.

Almost all of the heads have the same face and profile, as if they had been carved with reference to a single model. For a long time, it was assumed that they did not reach far below the earth but when one of them was excavated, it was nearly 16 m tall. The largest of all moai, with an impressive length of 20.65 m and weighing an estimated 250 tons, is located under a rock shelter.

These dimensions are astonishing and it remains unclear how the builders were able to move the statues from the rock and transport them to the slopes of the volcano. One theory asserts that they were transported on rollers and lowered with ropes; holes that may have been used to anchor the dowels can still be seen. Then the statues are thought to have been set down in prepared pits on the slope so that the planks on their backs could be removed and their forms chiseled out more precisely. The hundreds of pits were a great engineering challenge as well. The statues were then transported to their final location; the method remains another controversial issue for researchers. How were the builders able to move the 40 – 150 ton moai from the quarry to the platforms on the three coastlines? In experiments, the two best-known theories were tested: the transport of prone figures with rollers on wooden tracks and the transport of the upright figures with sleds in a wooden scaffold. Both methods proved practicable, provided that thousands of workers were available.

Possible transport routes were also found, some of them leveled, others filled and elevated or partly paved. At their destinations, the moai were pulled onto the ahu platforms and erected with ramps that were created by piling up stones (much like Stonehenge, see Fig. 6.43).

However, according to the legends of the Rapa Nui, it was their ancestors‘ magic that made the moai move to their ahu platforms on their own in the moonlight (page 391).

Ahu – stone platforms

The enormous stone platforms are called ahu and I find them even more exciting than the moai in relation to Atlantis because parts of the stonework show the same polygonal construction found in Giza and Peru (Figs. 5.14 -18).

Similar ceremonial platforms can be found on many Polynesian islands (Hawaii, Tahiti, Bora Bora, the Marquesas Islands and the Cook Islands), supporting the theory of settlement from the west. The term “ahu” is also used on the Marquesas Islands, the Tuamotu Archipelago and the Austral Islands, but only for the elevated platform that forms the border of a square marae (ceremonial area). On Rapa Nui, “ahu” refers to entire ceremonial complexes located along the coast within 500 m of the tidal line. Only seven of the 255 ahu known today are located inland, 164 of them with and 91 without moai statues.

An ahu was, and remains, a ceremonial site for the islanders, a spiritual connection between this world and the hereafter of their deities and ancestors, which is manifested in the structure and the statues. As they do on Moruroa/Tahiti, the ahu give the people a strong spiritual connection and power (mana) and absolute protection from enemies and evil spirits (tapu). They were always strictly spiritual and ceremonial sites but their courtyards were also used for ritual celebrations and political meetings.

From an engineering point of view, ahu are ramp-shaped stone piles with several steps and meter-high external walls. On the coastal side, that were built far more solidly and precisely than the other three external walls, which inspires the theory that they were added later.

Some ahu, such as Tahira Vinapu, have enormous megalithic walls that were built from large, perfectly cut blocks joined without mortar so that not even a razor blade fits between the stones (much like the structures in Giza and Peru, see Figs. 8.21-24). For most of the simpler complexes, much smaller unhewn natural stones were used. The bordering, leveled area contains a courtyard in front of the ahu, a sloping ramp paved with poro (pebbles) and an elevated square platform. Almost all of these altar-like platforms were also arranged to face the sunrise at the summer and winter solstices and the spring and autumn equinoxes. This confirms that these indigenous people had astonishing astronomical knowledge, as was the case at almost all of the earth‘s main power places.

Of the 255 ahu platforms, 164 served as foundations for the colossal moai and bore several statues (Ahu Tongariki had 15), together weighing hundreds of tons. Cylinder-shaped foundation stones were set into the surface of these platforms; the moai were erected on them and wedged with smaller stones. The ahu of Easter Island were typically located between a village and the coast, facing the settlement, with their backs to the ocean. Today, researchers think that every family built its own complex. There was a clear hierarchy determining the distance between the family‘s houses and the ahu. In her book “The Mystery of Easter Island”, Katherine Routledge, who visited Easter Island around 1920, categorized the ahu into four types based on how they were erected and furnished. Her categories are still relevant, although some researchers have subdivided them:

– Rectangular ahu without moai statues

– Ahu with statues (image ahu), stone-faced, raised platforms filled with soil and gravel

– Semi-pyramidal ahu of unhewn stones shaped like a flat pyramid with several steps, without statues

– Ahu Poe, also without statues, with the same pointed oval foundation as the canoes or Pangaea houses (Fig. 8.46)

Recent theories posit that the last two types were ossuaries for a funereal cult. The reason for this is that archaeological excavations in the 1980s and 1990s revealed that some ahu courtyards (but not the megalithic cores) had small chambers containing bone fragments that had presumably been moved there in a secondary burial after the corpses had decayed on the courtyards themselves. The bodies may have been buried there much later, as we have seen at Stonehenge, for example.

Note:

I also share the opinion that several construction phases must be distinguished here. Routledge considers the simply-built, square ahu without statues to be the oldest configuration and Ahu Poe Poe the most recent. But I consider the megalithic walls to be the first construction phase, then the ahu with moai and pyramidal shapes and finally, the square and pointed oval ahu without figures that are far more primitive than the others. Again, it seems to be an attempt by the descendants to recreate the original megalithic complexes.

This is just a small excerpt from the book GAIA LEGACY.

8. RAPA NUI, Easter Island (Chile)

8.1 Landscape 353

– Geography 353

– Geology 354

– Climate 356

– Vegetation 357

8.2 Power place 359

– Names 359

– Geomancy 359

– Power point 359

8.3 Constructions 360

– Main structures 360

– Subterranean structures 376

– Other structures in the region 377

– Temple structures 380

8.4 History 381

– Historical history 382

– Finds 385

– Prehistoric history 386

– Builders and peoples 386

– Original purpose 387

– Legends and myths 389

8.5 Spirit 391

– Religions and deities 391

– Spirituality and transmissions 394